Dazzling and Exquisite

Collecting was a fashionable activity among the imperial family of the Qing Dynasty, and they gathered many antique curios and scholarly accoutrements. The imperial family had a wide variety of curio display cases and boxes – known as duobaoge and baishijian – made for the explicit purpose of keeping this large collection of precious objects and showcasing their beauty and value. These were extremely fine works of art, and the vessels for storing and displaying these exquisite items were likewise superbly crafted. Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty was notably an avid collector and displayer of scholarly accoutrements and antique curios.

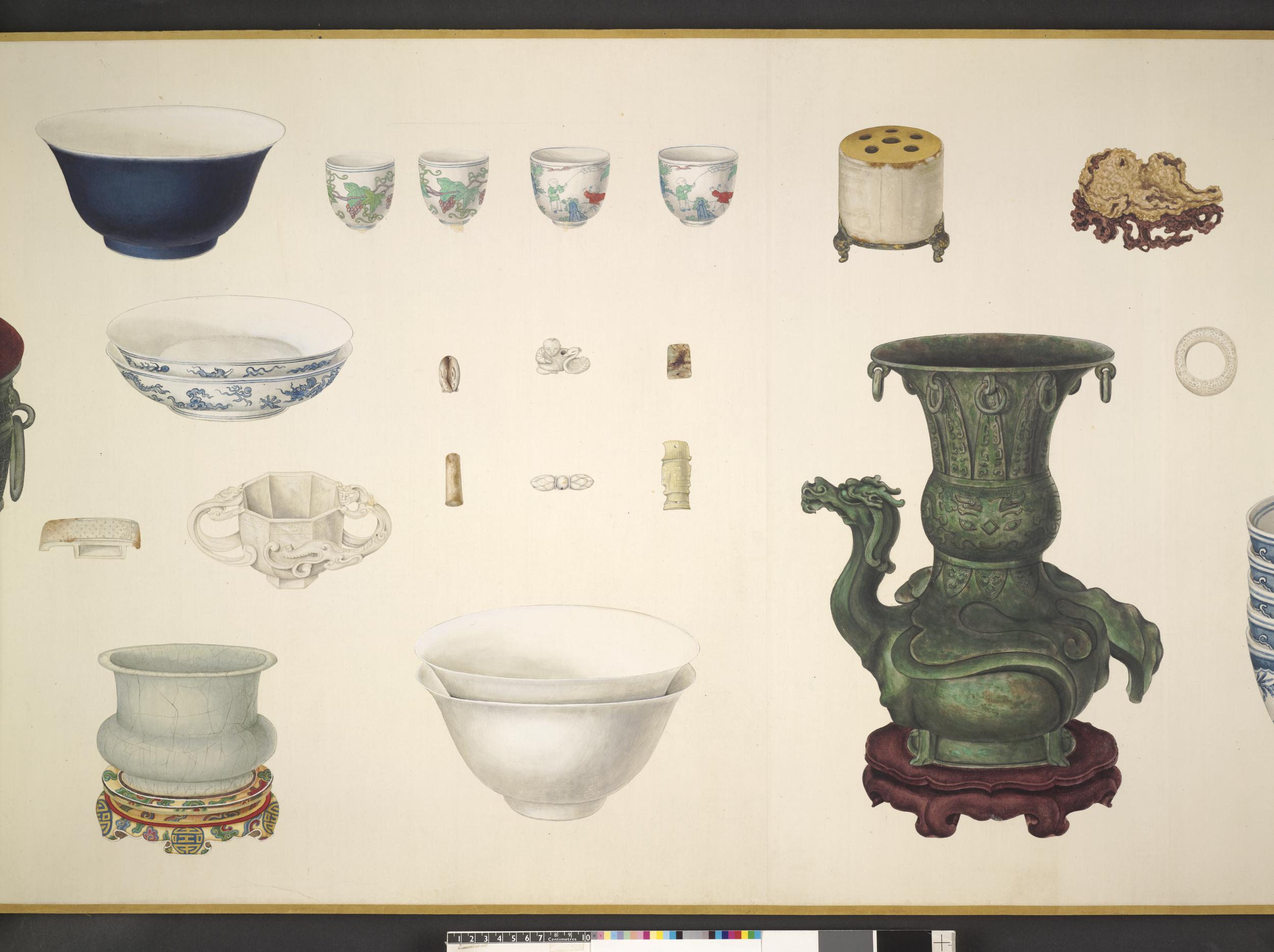

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

The folding screen behind the throne in the painting looks like a large rack, featuring a wide array of antiques. This largely resembles the Curio display case in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing. This Scroll of Antiques can be regarded as an illustrated catalogue of antiques in the Qing Dynasty.

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

The folding screen behind the throne in the painting looks like a large rack, featuring a wide array of antiques. This largely resembles the Curio display case in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing. This Scroll of Antiques can be regarded as an illustrated catalogue of antiques in the Qing Dynasty.

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

Scroll of Antiques, Emperor Yongzheng, Qing Dynasty

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

The folding screen behind the throne in the painting looks like a large rack, featuring a wide array of antiques. This largely resembles the Curio display case in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing. This Scroll of Antiques can be regarded as an illustrated catalogue of antiques in the Qing Dynasty.

Collection of Antiques and Treasures

The emperors of the Qing Dynasty had a passion for Han culture and continued the Ming Dynasty’s custom of appreciating antiquities. Duobaoge (‘boxes of many treasures’) curio boxes, which were used for holding and displaying large items of treasures, were commonplace. Often a combination of cabinets, shelves and drawers, they made the perfect piece of furniture for displaying treasures in the Qing palace.

Reading by the Fireside, series of paintings on Emperor Yongzheng at leisure, Qing Dynasty

Reading by the Fireside, series of paintings on Emperor Yongzheng at leisure, Qing Dynasty

Provided by the Palace Museum

Dressed as a Han scholar, Emperor Yongzheng (1678 - 1735) is absorbed in his reading. On the left of the painting is an elegant and large cabinet of antiques. The rack in the upper part of the cabinet, fitted with drawers, railings and frames, forms compartments of varying sizes at different levels. Bronze ware, ceramics, imperial seals, rare books and scrolls of painting and calligraphy, much loved by the literati, are displayed in the compartments. These items are of different sizes, highlighting the ingenious design of the display case. In his leisure time, Emperor Yongzheng would relax and appreciate the treasures on the rack.

Lady Meditating among Antiques, Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong, Qing Dynasty

Lady Meditating among Antiques, Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong, Qing Dynasty

Provided by the Palace Museum

The Screen of Twelve Beauties depicts ladies when appreciation of antiques was popular in the Imperial Palace. The large curio display case in the painting displays a curio collection representative of different periods, highlighting the adoption of Han culture by the Manchus of the Qing regime. It suggested their succession of the longstanding tradition and therefore, the legitimacy of their rule. These large display cases were indeed important furnishings in the Forbidden City for displaying treasures. They were not created by painters out of imagination but were modelled on real objects. Interesting that matching items can be found in the Imperial Palace in most cases.

Bronze gu vase, Shang Dynasty

Bronze gu vase, Shang Dynasty

Provided by the Palace Museum

On the left of the third shelf, right side of the scroll Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong, Qing Dynasty

The gu vase is a wine container. This vase is elegantly shaped, decorated with thunder pattern as ground and animals on it from the waist down.

Plain Narcissus Basin with Greenish-blue Glaze, Ru ware, Northern Song Dynasty

Plain Narcissus Basin with Greenish-blue Glaze, Ru ware, Northern Song Dynasty

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

On the left of the third shelf, left side of the scroll Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong

The Ru kiln is known as the leading kiln among the five famous kilns of the Song Dynasty and is famous for its greenish-blue ware, a colour known as “the sky after the rain”. Agate is added to the glaze, resulting in a warm lustre.

Monk’s cap jug in ruby red glaze, Xuande period (1426 –1435), Ming Dynasty

Monk’s cap jug in ruby red glaze, Xuande period (1426 –1435), Ming Dynasty

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

On the left of the second shelf, right side of the scroll Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong, Qing Dynasty

Ruby red glaze is the top red glaze created during the Xuande period (1426 –1435) of the Ming Dynasty. Bright as mirror with a jade like lustre, it has the resplendent stateliness of a ruby, hence its name. With a shape that gives the design its name, the monk’s cap jug first appeared in the Yuan Dynasty.

Screen with carved zitan hardwood frame and base inset with jade, Qing Dynasty

Screen with carved zitan hardwood frame and base inset with jade, Qing Dynasty

Provided by the Palace Museum

On the left of the second shelf, left side of the scroll Screen of Twelve Beauties Inscribed by Prince Yong, Qing Dynasty

After Emperor Qianlong had conquered Xinjiang, a lot of jade stones were brought to the Forbidden City and made into exquisite jade ware. Zitan wood is hard and does not change its shape or crack easily, and was greatly favoured by the imperial household. This screen is meticulously carved and finely executed.

Curio display case, Shufang Zhai (Studio of Cleansing Fragrance)

Curio display case, Shufang Zhai (Studio of Cleansing Fragrance)

Provided by the Palace Museum

A sizable curio display case is still in use, taking up the entire length of a wall. The curio are displayed in modern time.

Portable Collection

This space-saving box design is called baishijian, or “(holding) hundred odd items” and can usually hold dozens or even hundreds of artefacts. It therefore occupied an important position among the displays in the Qing palace. Besides being easy to store and carry, their complex and sophisticated designs give viewers the pleasure of finding and exploring treasures. They had therefore won the favour of the emperors of the Qing Dynasty. The baishijian boxes were akin to small safes – they were used for storing antiques, paintings, calligraphy and artefacts of the time, as well as cultural relics from Japan and the West. Emperor Qianlong attached great importance to their design and production. He once issued a decree ordering the existing baishijian to be presented to him every fifth day of the month, and on the twenty-ninth day if the month was short. He also enjoyed the process of designing the boxes himself.

Zitan hardwood box inset with plaques of antiques, Qing Dynasty

Zitan hardwood box inset with plaques of antiques, Qing Dynasty

Height: 46.4 cm Width: 42.3 cm

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

The box is made of zitan hardwood, with the frame in front inlaid with silver threads. It features large enamelled porcelain panels depicting antique items. There are wooden drawers and jade album leaves inside the box, with designed interspersing drawers and hidden drawers. The curios in the box include carvings of rhinoceros horns, bronze ware, ceramics, jade ware, Japanese lacquer and Western pocket watches, a good example of the rich content of a treasure box.

Zitan hardwood treasure box with bamboo threads and revolving compartments, Qing Dynasty

Zitan hardwood treasure box with bamboo threads and revolving compartments, Qing Dynasty

Height: 24 cm Diameter: 18.7 cm.

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

When the treasure box is opened, the cylinder turns into four equal pieces and resembles a small screen with four posts. There are numerous small compartments inside with wooden bases for displaying jade ware. There are also drawers, arc glass paintings of Western buildings and decorative posts made by Western lathe. Jade ware is displayed on revolving compartments, again demonstrating the superb skills of craftsmen during the Qianlong period.

Zitan hardwood treasure box with bamboo threads and revolving compartments

Height: 24 cm Diameter: 18.7 cm.

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

When the treasure box is opened, the cylinder turns into four equal pieces and resembles a small screen with four posts. There are numerous small compartments inside with wooden bases for displaying jade ware. There are also drawers, arc glass paintings of Western buildings and decorative posts made by Western lathe. Jade ware is displayed on revolving compartments, again demonstrating the superb skills of craftsmen during the Qianlong period.

Zitan hardwood treasure box with bamboo threads and revolving compartments

Height: 24 cm Diameter: 18.7 cm.

From the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

When the treasure box is opened, the cylinder turns into four equal pieces and resembles a small screen with four posts. There are numerous small compartments inside with wooden bases for displaying jade ware. There are also drawers, arc glass paintings of Western buildings and decorative posts made by Western lathe. Jade ware is displayed on revolving compartments, again demonstrating the superb skills of craftsmen during the Qianlong period.

Traveller’s box of scholarly items, Qing Dynasty

Traveller’s box of scholarly items, Qing Dynasty

Length: 74 cm Width: 29 cm Height: 14 cm

Provided by the Palace Museum

This is the “folding desk with miscellaneous items for travellers” in the records of the Imperial Workshop, or portable container of miscellaneous items. Made of zitan hardwood, the box is compact when tightly closed. When opened, the surface of the box forms the desktop, with the legs unfolding from within the box. There are two drawers of the same size in the box, each with two layers of different compartments for storing a total of 64 mini sized scholarly and miscellaneous items. The compartments are of different sizes specially designed to fit the size of the items, and each item has its designated place.

Collection of Arts and Crafts

If curio display cases and treasure boxes display curios, then this item named “multiple glazed monumental vase” displays craftsmanship. It encompasses almost all major types of glazes in the ceramics history of China as encyclopedia of craftsmanship, including gold, cloisonné, famille rose, blue and white, and glazes in imitation of those of Ru, Guan, Ge and Jun ware of the Song Dynasty. On the body, there are as many as 15 different glazes. Due to multiple types of glazes with different properties, materials and formulations, the temperature and oxygen requirements during firing in the kiln are different. Precise control of every detail is essential, and the firing process is highly complicated. The chance of success of making such a vase is very low. This design and the demand on techniques are unparalleled in the history of ceramics as if Emperor Qianlong conducted an experiment of craftsmanship. It can be seen that techniques on paste, glazes, painting and firing was fully mastered at that time.

Multiple Glazed Monumental Vase, Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty

Multiple Glazed Monumental Vase, Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty

Height: 86.4 cm Diameter of the mouth: 27.4 cm Diameter of the foot rim: 33 cm

Provided by the Palace Museum

There are 12 rectangular panels on the body of this vase, six of which depict auspicious scenes, including “three rams bringing bliss”, “elephants carrying vases”, “boy striking the fou”, “hills and residence of the immortals”, “phoenix and the rising sun”, and “nine dings”. The other six include the Buddhist swastika on patterned background, the bat, the auspicious beast panchi, the plant lingzhi, flowers and ruyi, also bearing auspicious meanings of abundance, blessings, warding off evil, longevity, prosperity, and wishes coming true. The various pictures, matched with different glazes, are dazzling and make a feast for the eye.